![]() ome of the guys over at the B&B Pitstop Cafe were

arguing the other day about “suckers” in corn. The older fellows

remember being sent to the fields as kids to pull “suckers” off the

corn plants because their fathers believed that “suckers” were bad

for the corn; although some suspected that the real purpose may have been to

simply keep them out of their father's hair on hot, muggy summer days. Well,

what are “suckers” and are they bad for corn?

ome of the guys over at the B&B Pitstop Cafe were

arguing the other day about “suckers” in corn. The older fellows

remember being sent to the fields as kids to pull “suckers” off the

corn plants because their fathers believed that “suckers” were bad

for the corn; although some suspected that the real purpose may have been to

simply keep them out of their father's hair on hot, muggy summer days. Well,

what are “suckers” and are they bad for corn?

“Suckers” Are Tillers

“Suckers” Are Tillers

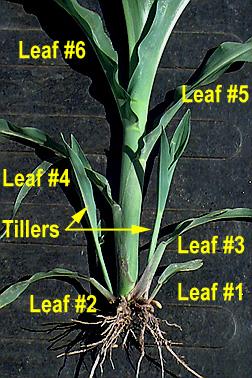

Tillers are basically branches that develop from axillary buds at the lower five to seven stalk nodes of a corn plant. Tillers are morphologically identical to the main stalk and are capable of forming their own root system, nodes, internodes, leaves, ears, and tassels.

Similar axillary buds at nodes higher up on the main stalk initiate ear shoots rather than tillers. Ear shoots differ morphologically from tillers in that internode elongation (within the ear shank) is less, leaves (husk) are shorter, and the stalk (ear shank) terminates in an ear (female inflorescence) rather than a tassel (male inflorescence). Sometimes, however, a tiller becomes “confused” during its development and generates a terminal inflorescence that is partially male and female (aka “tassel-ear”).

Most agronomists agree that tiller development in field corn represents a signal that growing conditions are quite favorable, with ample available levels of nutrients, water, or sunlight. Such favorable growing conditions may exist simply due to favorable weather conditions or because the field’s plant population is low relative to the yield potential of the field. With favorable growing conditions, the corn plant has ample energy and nutrients to “invest” in tiller development. Some hybrids are also genetically prone to developing tillers, even at adapted plant populations. Tillers may compete somewhat with the main stalks, but given their usual late developmental start they usually lose out in the competition for water, nutrients, and light.

Tillering

In Response to Damage

Tillering

In Response to Damage One or more tillers commonly form if the main stalk is injured or killed by hail, frost, insects, wind, tractor tires, little kids' feet, deer hooves, etc. early in the season. If the damage occurs early enough in the growing season, tillers may actually develop harvestable ears. Late developing tillers, however, usually don’t have enough time to develop ears that mature before a killing fall frost. An example of late tillering occurred in some Indiana fields severely damaged by the late June frost of 1992. The apparent “recovery” of these fields looked promising from “windshield surveys”, but little if any grain yield was obtained from these damaged fields.

As a rule, the net effect of tiller development in an undamaged field is neutral. Most recent research suggests that removal of tillers has little, if any, effect on corn grain yield. Usually, the main stalk will “outcompete” the tillers and the tillers eventually wither away. Tiller development in a field that was damaged or simply planted too thin MAY result in harvestable ears and thus contribute to grain yield.